Do you feel a “warm glow” inside when replacing an incandescent light bulb with an LED bulb, knowing that this small act helps the environment? Reports from the power industry and the environmental community clearly indicate that we are “saving power” when using LED bulbs. Great, right? Not so fast! Deeper thinking on the overall impacts of conservation is needed.

“Do what’s right. Turn off the light!” Starting a conservation debate.

There are wonderful conservation efforts in the United States and other countries where environmentally-minded citizens participate in slogan-driven campaigns like “Do what’s right, Turn off the light!”. Could there be any campaign with so pure an intent and so predictable an outcome? What could possibly go wrong? What if I asserted that the result of conserving might be the exact opposite of what was intended – in this case environmental damage in the form of emissions?

There are wonderful conservation efforts in the United States and other countries where environmentally-minded citizens participate in slogan-driven campaigns like “Do what’s right, Turn off the light!”. Could there be any campaign with so pure an intent and so predictable an outcome? What could possibly go wrong? What if I asserted that the result of conserving might be the exact opposite of what was intended – in this case environmental damage in the form of emissions?

A “perverse” outcome – the opposite intended outcome occurs.

We can construct a simple conservation example illustrating a perverse outcome using the slogan “Do what’s right Turn off the light!”. Leave a room and flick the switch off. This seemingly virtuous act conserves power, and reduces emissions by avoiding the burning of fuel. Could turning off the light result in greater environmental damage? The answer lies in the complex interaction between socio-ecological behavior and economics.

The near-term desired result is lowered emissions by not burning a chunk of coal (fuel). However, that bit of carbon-based fuel, now discounted on the international supply and demand curve, can still be purchased by a power company, foreign or domestic who can burn it, and then sell the discounted power generated to an auto manufacturer. The now-burnt discounted coal lowers the cost of goods for the manufacturer which results in lower cost autos, and allows the car manufacturer to increase sales which generate even worse carbon emissions in the long-term! Because I didn’t use the coal, it became cheaper for someone else to burn it and use it.

My example describes a tiny effect and I’ve mixed macroeconomics and microeconomics making economists roll their eyes. However, imagine if a country reduced the power needed by the residents through campaigns like turning off unused lights in homes, or simply by making power plants more efficient. If there are no other constraints in that free market system, then anyone can use the now cheaper fuel for their own purposes. It is possible that this results in increased industrial output of products that in turn will use more fuel. This is the opposite of the desired effect when we flicked the light switch off or increased the efficiency of a society’s power use!

Should we burn as much power as possible by leaving our incandescent bulbs burning and avoid the “perverse effect”? Burn it before someone else uses it? Of course not, but before proposing possible solutions, let’s delve into this more deeply.

Systems with humans? Complex…

In my transition from high-tech to sustainability, I have been struck by the frequent unintended consequences from deliberate human actions in environmental systems. Early in my career, I designed complex electronic products by “modeling the system” before manufacturing it. Unintended consequences were minimized using accurate models that predicted how electrons flow, and there was no need for human behavioral modeling.

Modeling human behavior is complex. We interact with natural and manmade systems in ways that generate counterintuitive and unpredictable results. Imagine building a system model including humans for something as simple as an Orange County, CA campaign to conserve water (inset below). The complexity is apparent and a seemingly virtuous action results in a surprise.

Studying the “Oops” effect.

The frustration caused by unpredicted consequences from purposeful human actions has attracted sociological researchers throughout history. In the early half of the 20th century, Robert Merton of Harvard pushed for a more rigorous analysis of unintended consequences, “the treatment of which has [for too long] been consigned to the realm of theology and speculative philosophy”. Merton used a statistical model for human choices, and derived probable outcomes (Merton, 1936, pp. 898-904). He identified three types of consequences:

| Merton’s Defined Outcomes from Purposeful Human Actions | |

| Unintended benefits | Unpredicted “good” effects |

| Unintended drawbacks | Unpredicted “bad” effects |

| Perverse effects | Outcome opposite of expected, elicits a “What the …?” |

Those unintended drawbacks and perverse effects are the focus of this blog post.

Efficiency and a paradox asserted by Jevons.

Modeling human behavior in a system includes choices made in a free market that is built on maximizing efficiency. In a capitalist system, the most efficient manufacturer or provider of services has a cost advantage over a competitor. The coupling is so tight, that it is hard to determine if capitalism drives efficiency or vice-versa! If our country conserves energy, for example, it is another way of saying that our society is more efficient. We are living and using less power. Sounds great, right! Not so fast!

Over 150 years ago, William Stanley Jevons, a British economist, was studying the coal and steel industry in the United Kingdom. He stated something so startling and counter-intuitive that we still haven’t really absorbed the meaning. Here is Jevons’ statement:

Over 150 years ago, William Stanley Jevons, a British economist, was studying the coal and steel industry in the United Kingdom. He stated something so startling and counter-intuitive that we still haven’t really absorbed the meaning. Here is Jevons’ statement:

It is wholly a confusion of ideas to suppose that the economical use of fuel is equivalent to a diminished consumption. The very contrary is the truth.

– William Stanley Jevons, British Economists and Logician(Jevons, 1866, p. 123)

He asserted that improved efficiency using fuel doesn’t reduce overall consumption, it increases it – a paradox!

Spreading Jevons’ paradox around a bit.

This paradox doesn’t just apply to fuel. Costs go down as efficiency increases, which stimulates increased demand. Conservation efforts, as defined by those that are concerned with the environment, is a form of efficiency – when we ask our society to use less (waste less) it makes our usage efficient.

Based on our “turning off the light example”, you can see that if I or anyone else uses less energy, water, fuel, or food, that commodity can be used by someone else or some other entity. In a free-market system, we simply lowered the cost for others who may want to use the commodity. Enterprising companies or creative individuals may even find new uses because of lower costs.

The paradox – an airline example.

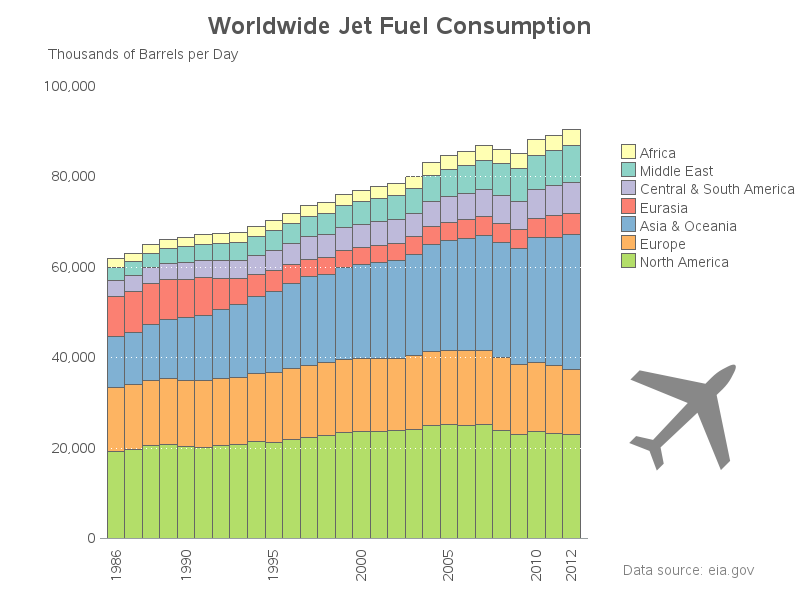

Over the history of airline growth, jets were made more efficient:

- Jet engines use half the fuel required in 1960 – twice as efficient.

- Airlines pack more people in per square foot (argghhh!) reducing the flying costs per person.

- Aerodynamic changes to jet shapes reduce fuel consumption

Figure 1 Jet fuel usage from 1960-2012

The result is that flying costs less, and many more people fly. According to Jevons, jet fuel usage worldwide increases beyond what was used before the efficiencies were obtained (Figure 1). For a conservationist this is a form of the perverse effect if the desired outcome for increased efficiency was to use less jet fuel worldwide.

Is the paradox real?

Does everyone agree with Jevons? Remember what I stated about complex systems at the beginning of the blog? Socio-economic behavior is complex, and when we try to predict worldwide behavior, it’s even more complex. Economists have argued against the paradox since Jevons stated it. Most of the arguments are about whether it is truly a “perverse” effect so economists came up with a term called “rebound” which allows the usage of fuel for example to be less, the same, or more than before the efficiency was obtained. Remember, Jevons unequivocally said it would be more.

Forward into uncertainty, and possible solutions.

In my opinion, this paradox needs careful study since the impact is profound for sustainability. A deeper understanding will result in more effective conservation solutions.

For example, if Jevons is correct, then only regulation limiting production or consumption will constrain the capitalistic system to avoid the perverse effect from conservation actions. These concepts may be abhorrent to industry and many in society. One method of limiting production is by capping emissions or power generation. Another method is adding a tax to raise costs for the consumers. These taxes could be used to pay the costs of environmental impact that are not borne by industry, and paid anyway by society years later when impact is better understood.

Practical concerns abound that will test our belief systems.

In addition, these issues affect the global economy and any regulation of the market by any country requires enforceable global treaties. Imagine the effect if the US unilaterally capped power generation. It’s a windfall of cheap energy for a country that doesn’t cap. This is one concern that prevents the US from joining the climate change accords.

Real conservation and environmental sustainability strike deep at fundamental belief systems in economics, morals, faith, and governance. Solutions for sustainability will come from all sides – economists wrestling with capitalism, regulatory agencies using wise enforcement, and faith communities embracing stewardship. Sustainability efforts must consider impacts many generations into the future. The present polarization of beliefs, and isolation of groups and countries are the opposite of “systems thinking” and must end for achieving practical solutions.

The call and the ask.

New socio-ecological models account for the layered and complex larger systems, thus allowing better prediction of overall consequences (Janssen et al., 2006; Larrosa, Carrasco, & Milner-Gulland, 2016). These models inform decision makers, and allow for integrated policy that incorporates societal, business, governmental, and environmental behavior modes. In some respects, we are just beginning the understanding of human system modeling. It is an exciting time!

How can you engage in real sustainability? First, it is ok to feel that “warm glow” inside when turning off a light, or using LED bulbs! Conservation is a necessary part of the solution, but it is not sufficient. Our world needs a deeper understanding of conservation effects just as Jevons asserted in 1866! Simple slogans still work for individuals and communities. Simple slogans must also be applied to the larger system which includes industry and countries. “Cap industry emissions!” may be just as necessary as “Turn off the light!”. This is a call to the deep thinkers. Our ability to sustain the planet requires understanding of extremely complex systems that include humans. If responses are respectful, please argue with me, or add examples and solutions. All of us may learn. Join the cause for understanding because future generations are depending on all of us. We need you!

Simple slogans must also be applied to the larger system which includes industry and countries. “Cap industry emissions!” may be just as necessary as “Turn off the light!”. This is a call to the deep thinkers. Our ability to sustain the planet requires understanding of extremely complex systems that include humans. If responses are respectful, please argue with me, or add examples and solutions. All of us may learn. Join the cause for understanding because future generations are depending on all of us. We need you!

References:

Janssen, M. A., Bodin, Ö., Anderies, J. M., Elmqvist, T., Ernstson, H., McAllister, R. R. J., … Ryan, P. (2006). Toward a Network Perspective of the Study of Resilience in Social-Ecological Systems. Ecology and Society, 11(1), 15.

Jevons, W. S. (1866). The coal question; (2d ed.). London: MacMillan and Co. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015013153351

Larrosa, C., Carrasco, L. R., & Milner-Gulland, E. J. (2016). Unintended Feedbacks: Challenges and Opportunities for Improving Conservation Effectiveness. Conservation Letters, 9(5), 316–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12240

Merton, R. K. (1936). The Unanticipated Consequences of Purposive Social Action. American Sociological Review, 1(6), 894–904. https://doi.org/10.2307/2084615

Shine, N. K. (2015, September 1). ‘Brown is the new green’ as grassy medians go by the wayside amid drought. Orange County Register. Retrieved from http://www.ocregister.com/2015/09/01/brown-is-the-new-green-as-grassy-medians-go-by-the-wayside-amid-drought/

Stevens, M. (2015, September 1). Unintended consequences of conserving water: leaky pipes, less revenue, bad odors. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from http://www.latimes.com/local/california/la-me-drought-consequences-20150901-story.html